| | Fall seeding for pasture | Spring seeding for pasture | Interseeding | Double cropping | Hay and silage | Grazing and feeding problems | Feeding rye grain to livestock

Fall rye is a very versatile crop when it is used for forage. It can be effective as weed control as it grows very competitively and, in the vegetative state, can become very leafy. It can be used for pasture, hay or silage, but the majority of fall rye is seeded for summer, fall and spring grazing. It can be seeded throughout the spring or summer and utilized the year of seeding for pasture as well as the following year for pasture, silage or grain production, depending on grazing management.

Forage production of fall rye may not be as high as for some other cereals, but its ability to withstand grazing and the winter hardiness of the crop allow it to be used as a forage for more than one year in most areas of the province.

The current varieties of fall rye listed are all winter hardy and include Hazlet, Bono, Brasetto, Guttino and Prima. Hazlet and Prima are both open pollinated varieties and are best suited for grazing, while the others are hybrid varieties with higher yields best suited for grain production, primarily for milling or distilling.

Fall rye will produce best when grown on fertile, well drained soils of medium texture. However, when grown under less ideal conditions, such as soils with high acidity, low fertility or heavy and light textured soils, fall rye will generally outyield other commonly grown cereals.

When grown for pasture, fall rye should be seeded at 55 to 110 lb/acre (drier areas should use a lower seeding rate). The plant’s ability to tiller profusely under good growing conditions makes this crop an effective pasture. It can be grazed once the roots are established and a good ground cover has developed through tillering. At this time, the plants should be 6 inches high. Fall rye can grow substantially under cool temperatures and is suitable for fall and early spring grazing.

The nutrient level of fall rye for pasture is excellent. Protein levels will vary with the amount of soil nitrogen and growing conditions, but a dry matter protein content of 18 to 23 per cent can be expected. Fibre levels are generally 25 to 30 per cent. At Brooks, (irrigated) spring seeded fall rye had a higher protein content throughout the summer than oats, barley or utility wheat. Fall rye sampled the end of October still had a protein content of 22.4 per cent. The fact that fall rye can maintain quality late in the season makes it a good late season pasture.

Fall rye is also an excellent choice to use when taking out old pasture or hayland. Research by the Western Beef Development Centre at Termuende demonstrated that fall rye seeded by zero till drill after spraying an old hay field with glyphosate provided good quality fall and spring pasture. Fall rye can be used effectively to take out unproductive, old hayland and pasture before seeding to other annuals or perennials again. Of course, productivity depends on moisture and fertilizer applied to the soil.

Fall Seeding for Pasture

Generally, fall rye is seeded August 1 to 15 for good fall grazing. This window for seeding allows the crop to become established, so it can provide quality pasture well into the fall. Few forage crops can match the quality and production of fall rye in the fall. Avoid grazing so heavily that the ground is left bare; overgrazing will affect the next year’s production and winter survival and may lead to erosion.

Fall seeded fall rye provides earlier spring grazing than other annual and most perennial pastures. Fall rye works well in pasture rotations for early grazing, until perennial pastures have enough top growth to graze. Fall rye is the most dependable winter cereal for winter survival. The key to spring grazing is to graze early and graze hard to prevent the fall rye from producing stems and seed.

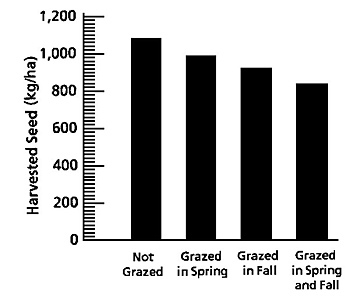

Fall rye, if heavily grazed in the fall or spring, will yield less silage or grain the following year (Figure 4). The effect of fall or spring grazing on seed or silage yields depends on winter conditions, soil type, temperature, moisture levels and fertility.

Figure 4. An average effect of grazing on subsequent grain yields.

Source: Agriculture Canada Research Station, Swift Current

A decision must be made at seeding as to the desired use of the crop. To be safe, if the fall rye is to be used for silage or grain the following year, keep fall and spring grazings to a minimum. The later in the spring the crop is grazed, the more it will yield for pasture but the less for silage or grain (Table 1). Grazing a crop of fall rye as the tillers are approaching the boot stage will greatly affect grain yield. The plant at this time is beginning reproductive growth rather than vegetative growth.

| Table 2. Spring Grazing of Fall Rye, Brooks |

| Date of Clipping | Mean Clipping

Yield kg/ha | Summer Hay (silage)

Yield kg/ha | Grain Yield

kg/ha |

| 1st week May | 1890 | 8930 | 3520 |

| 2nd week May | 3160 | 7520 | 2720 |

| 3rd week May | 5360 | 5410 | 1400 |

| 4th week May | 6090 | 5370 | 1540 |

| 1st week June | 6050 | 3310 | 1115 |

| 2nd week June | 5560 | 4910 | 1830 |

| Control | 0 | 9010 | 3470 |

Source: Proceedings of Alternative Crops Conference, Lethbridge, Alberta. To convert kg/ha to lb/ac, multiply by 0.89.

Spring Seeding for Pasture

Fall rye seeded in the spring has the advantage of providing summer and fall pasture in the year of seeding as well as in the following year. Spring seeded fall rye works well as a rotational pasture. If grazed heavily with a long rest period between rotations, it will yield more than if it were grazed with a short rest rotation or continually grazed. It can be grazed every three to four weeks depending on fertility and rainfall.

Research at Swift Current has shown that daily gains in cattle are higher when the fall rye has been grazed less. What fall rye lacks in quantity of production is made up for in quality. Overgrazing at any time will severely reduce the regrowth ability and future production.

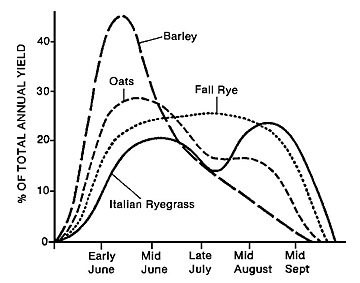

Early production of spring cereals is higher than spring seeded fall rye (Figure 5), but production of these crops declines rapidly in mid-summer. Adding 25 lb of oats or barley to the fall rye will increase the pasture yield early in the season and allow 7 to 10 days earlier grazing.

In trials at Brooks, average yields of fall rye in a simulated pasture rotation under irrigation yielded 3.2 tons/acre (dry matter) of forage. In Lacombe, a simulated pasture trial yielded 1.8 tons/acres (dry matter) of fall rye for forage. These yields may not be duplicated in the field since there will be yield losses caused by trampling. Soil fertility, soil type and rainfall will all have an effect on the yield.

Interseeding

Figure 5. Typical seasonal distribution of pasture yield*.

* Caution: lines do not represent actual yields but indicate typical growth pattern of the crops.

Fall rye can be spring seeded with oats and or barley for silage or grain. Yields of these crops may be reduced by the competitive nature of fall rye. Crops for silage may be less affected since they are harvested early, and vegetative growth is less affected by competition than in grain formation. The reduction in yield is variable and depends on soil moisture, fertility and soil types.

The underseeded fall rye can be used for pasture after the spring crops have been harvested. The amount and quality of rye regrowth is good when used in this manner. If the silage or grain crop is more important than the fall rye for pasture, the fall rye seeding rates should be decreased by one quarter to one half the regular seeding rate. However, lowering the fall rye seeding rate will reduce the pasture yield.

The spring companion crop chosen will also affect the yield of fall rye for pasture. Oats are generally less competitive than barley and should be considered if the fall rye is important for pasture during the year of seeding. Oats may also have more regrowth than barley when the crop is grazed after harvest, although the competitive nature of the fall rye will greatly affect the regrowth of the other cereal.

The fall rye can be overwintered and used for pasture silage or grain the following year.

Fall rye and fall triticale exhibit greater resistance to diseases, such as barley yellow dwarf, than winter wheat when grown in this manner.

Double Cropping

Fall rye has been seeded into freshly harvested grain stubble or cereal silage stubble and successfully utilized for fall pasture. If the fall rye is seeded directly into the stubble without cultivation, the stubble will hold the snow and provide better cover during the winter and may improve winter survival.

When following this double cropping procedure, select an early maturing spring sown variety to facilitate early seeding of the fall rye. Double cropping is generally only acceptable for pastures since there will be volunteer grain in the fall rye the following spring.

The success of double cropping depends on soil moisture and weed populations. It may also be advantageous to double crop soils susceptible to erosion.

Hay and Silage

Fall rye for silage or green feed production is ready early in the season if it is not grazed in the spring. This approach allows the producer to spread out the silage season.

The harvest stage for fall rye as green feed or silage depends on feeding requirements. If intake and animal performance are critical, fall rye should be harvested at the flag leaf to flowering stage. Research1 has shown that fall rye harvested during this stage will have feeding qualities similar to that of barley in the soft dough stage. If harvest is delayed, fiber levels increase while palatability and intake decrease.

Feeding trials conducted at the University of Saskatchewan indicated that the intake of fall rye harvested at the soft dough stage was only 66 per cent of fall rye taken at the flower stage. This finding is substantiated by work done by Harshbarger et al in Illinois in 1956.

Of course, the earlier the crop is taken, the lower the yield. It may be more critical to take the crop early when making green feed as intake may be more restricted in dry feed than silage. Operators often notice this situation with oat green feed, which is usually more palatable than fall rye.

If the crop is allowed to become too mature, ergot bodies may be formed in the seed head. These ergot bodies may cause abortions in livestock if they are present in high enough concentrations. If ergot is a problem, the feed should be mixed or diluted with other feeds to reduce the concentration. Maximum allowable levels of ergot in grain for feed purposes is best provided by a test for alkaloid levels.

The quality of fall rye for silage is comparable to other cereals, whereas if it is cut for hay past the heading stage, it tends to be of lower quality, coarse and less palatable. When rye is cut late for silage or hay, protein content decreases and fibre content increases.

Yields of fall rye for silage or hay are generally lower than yields of oats or barley, but may be higher in areas or years where there is less rainfall and crops are stressed.

Fall rye is a winter cereal and has the advantage of utilizing good spring moisture; it resumes growth in the spring as the soil temperature permits. This feature makes fall rye an attractive crop for silage or hay on sandy soils or in drier areas of the province.

Grazing and Feeding Problems

Nitrate poisoning may be a problem when grazing or feeding fall rye silage or hay. If the crop has been stressed by frost, drought, hail or plant diseases, in combination with high levels of available nitrogen in the soils, nitrate can accumulate in the plant. This accumulation may become high enough to be toxic in livestock. The risk of nitrate poisoning will increase if the crop has been fertilized with high rates of nitrogen or planted on heavily manured fields. It should not be fertilized at rates higher than normal grain crops, unless the livestock and pasture are intensively managed.

Producers should be cautious if grazing or feeding fall rye that has been under severe stress. Livestock should be removed from the pasture or the silage or hay restricted until the feed has been analyzed. Nitrate levels in the feed over 0.35 per cent to 0.45 per cent are considered potentially toxic. This high nitrate feed may be mixed with safe feed to reduce the risk.

If nitrate levels are abnormally high in a pasture, take care to see that the fall rye is not the sole feedstuff. Animals can be fed grain or other high quality feeds prior to pasture exposure each day. Cattle grazing pastures with high nitrates can become somewhat acclimatized, over time, to moderate levels of nitrate in fall rye.

Grass tetany is another problem that may arise when grazing fall rye or other lush growing pastures, especially when heavily fertilized with nitrogen and potassium. This condition is caused by low levels of magnesium in the animal’s blood. Even though the herbage may contain adequate levels of magnesium, absorption may be low if there is an imbalance of other minerals. Grass tetany may be a risk if the ratio of potassium (K) to calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) in the herbage is greater than 2.2. Fertilizing pastures with magnesium or feeding magnesium may reduce the risk.

This condition can be recognized by nervousness and twitching by the animals; in the later stages, the animal may stagger, go down on its side and go into convulsions. If this problem arises, work closely with your veterinarian.

Having bales of hay or green feed out in the pasture when very lush conditions are present will reduce the risk of problems as well.

Overall, however, the adaptability, versatility and quality of fall rye make it an attractive crop to grow for livestock forage. It allows the producer flexibility while maintaining a high quality forage program.

Feeding Rye Grain to Livestock

Rye can be a highly nutritious, economical feed grain for livestock, but it has not always been popular with livestock producers or feed companies. Although some of their reasons for this discrimination are valid, most are unfounded. Admittedly, rye is less palatable to most livestock than other grains and is more susceptible to ergot. However, these conditions can be allowed for when setting up the feeding program or ration.

While it is important to be aware of the danger of ergot contamination, the concern should not be used as an excuse to condemn rye as feed. Most rye does not have enough ergot to be harmful, and when it does, it can be cleaned and/or diluted to safe levels.

Rye is similar to barley in its average nutritive content. It has about 12 per cent protein, 2.5 per cent fibre, 76 per cent total digestible nutrients (TDN) for cattle and 3,330 kcal/kg digestible energy for pigs. It has slightly less energy content than wheat or corn, but more than oats. Its protein content is lower than that of wheat. As with other cereals, rye’s nutritive content varies with growing conditions.

Rye appears equal to or slightly superior to barley in livestock rations, but using it to replace wheat has resulted in lower performance.

In research trials, dairy rations containing 40 or 60 per cent rye were fully equal to barley rations with respect to daily consumption and milk production.

In trials with finishing steers, rations containing 60 per cent rye were equal to rations containing the same amounts of barley.

In Manitoba tests with beef steers, rye was successfully used to replace all the cereal, and beef steers gained 2.86 lb/day.

In trials with growing-finishing pigs, replacing up to 30 per cent of the barley with low-ergot rye did not significantly reduce performance. Pelleting rations containing rye helped to reduce the depression in average daily gains that occurred when higher levels of rye were fed. Rye is not recommended for piglets.

Studies at Kemptville, Ontario, showed that rye can replace up to 10 per cent of the wheat in broilerfinisher diets with similar results. Higher levels reduced performance as wheat is higher in energy than rye. Diets for pullets, layers and breeder flocks can contain 10 to 20 per cent rye, but rye is not recommended for young chicks as it may cause watery droppings and pasty vents.

Although the evidence shows that rye is at least equal to barley in energy value when fed as part of the diet, animals often eat less when rye is the only grain, so performance suffers. This result is generally attributed to a lack of palatability. Animals do not like the taste of rye as much as other grains. This is not a serious problem in most cattle or sheep rations because rye is used as a concentrate along with other grains. Also, as beef cattle are often not fed for maximum grain intake, any effect on daily intake is not noticeable.

The palatability of rye is a greater problem with pigs and poultry. Rye should be analysed by a reputable feed laboratory and the ration formulated according to the results.

1. Stefanyshyn-Cote, Barbara Ann, "The Effect of Maturity and Ensiling on the Nutritional Quality of Fall Rye {Secale Cereale L.} Forage" University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, 1993.

More Information

For additional information see the Alberta Agriculture publication Fall Rye Production, Agdex 117/20-1.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to express a sincere thank you to Walter Yarish, Tim Ferguson, Ieuan Evans, Mike Dolinski, Doug Penney, J. Thomas, Don Salmon, Bob Nelson, Grant McLeod, Keith Briggs, Dave McAndrew, Myron Bjorge, Bob Wroe, Russel Horvey, Alan Toly, Bob Wolfe, Blair Shaw, Bill Chapman, Wayne Jackson, Larry Welsh, Ellis Treffry, Gordon Hutton, Allan Macaulay, Mike Rudakewich and Lu Piening for their constructive criticism in reviewing and improving this manual.

A special thanks to Arvid Aasen who wrote, with the help of Ken Lopetinsky, Vern Baron, Ellis Treffry and Myron Bjorge, the pasture, the hay and silage section.

Prepared by:

Murray McLelland formerly with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development

Revised by:

Harry Brook, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Source: Agdex 117/20-1. Revised June 2018. |

|